|

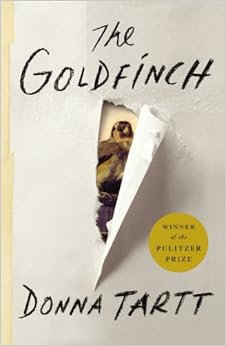

THE GOLDFINCH By Donna Tartt

Little Brown and Co. $30, 771 pages,

2013 Pulitzer Prize winner for Fiction

|

So begins Donna Tartt’s pulitzer-prize winning novel & literary blockbuster, The Goldfinch--the painting Theo absconds with to his E. 57th St. home where he expects to find his mom waiting for him. Unfortunately, Theo’s mother, Audrey, dies in the blast leaving him a quasi-orphan--alone with his trauma, his memories, his uncertainty toward the future, & his newly acquired, secret masterwork. This titular painting reminds Theo of his mother and constantly reminds readers of (among other things) its emblematic status for Art’s verisimilitude.

Interestingly, Dutch painter Carel Fabritius’s tragic death hangs over Tartt’s novel like the sword of Damocles. Fabritius studied under Rembrandt in Amsterdam; he's often compared to fellow Delft artist Vermeer (Girl with a Pearl Earring) and was killed by a gunpowder explosion in 1654 at the age of 32--the same year he deftly flicked out a relatively small piece called, The Goldfinch (13-1/4 in. x 9 in.).

Though the actual painting’s showcased with the Frick Collection in The Hague’s Mauritshuis’s Royal Picture Gallery, Tartt conveniently places the painting at the Met in New York for what becomes a clever parallel of destruction & redemption of both art & soul.

Two explosions: one in 1654 killing Fabritius; one in contemporary New York killing the protagonist’s mother. Tying them both together: the salvation of Fabritius’s tiny but illustrious painting, The Goldfinch--“It was a small picture, the smallest in the exhibition, and the simplest: a yellow finch, against a plain, pale ground, chained to a perch by it’s twig of an ankle.” Sometimes characterized by its trompe l’oeil illusionism, both the painting & the novel employ this stylistic flourish to imply a greater sense of perspective & symbolism. At once a symbol for the loss of his mother, The Goldfinch too reflects Theo’s condition of being un-caged but nonetheless tethered to circumstantial constraints. This is more sledgehammer symbolism than a subtle insinuation. And if the reader doesn’t get the all-too-obvious hint by the end of the novel, Tartt provides an unparalleled sermon that is at once muddled with contradictions & altogether unnecessary for perhaps even the most obtuse readers.

As an unmistakable Bildungsroman, The Goldfinch chronicles the misadventures of Theo, who after his saintly mother dies, is first tossed in with a posh upper-east side family, the Barbours--known for their discretion & repressed anxiety--; then, not shortly after, he is spirited away to Las Vegas by his prior absentee father--known for his abusive drunkenness & gambling; then, after a dubious set of circumstances leading to his death in a car accident--and the brilliant cultivation of a memorable friendship with a worldly-wise Ukrainian named Boris who teaches our young protagonist how to smoke, & booze, & bond, & drop acid (among other things)--; Theo, now parentless, vacates the Nevadan desert and its evanescent exurb back to New York where he finds himself bedraggled at the footstep of Hobie’s home/furniture restoration shop. Much of the novel, centers on Theo learning the furniture trade and filling in for the late-Welty as the unscrupulous sales manager. Tangled up in this almost-entirely linear tale, Tartt tosses in a seemingly unrequited love interest with an tangential character named Pippa who also survived the terrorist bombing at the Met.

Without giving too much away, Theo’s fraudulent dealings come to light and, as a result, is blackmailed by a man who suspects Theo has one invaluable, thought to be destroyed, painting by Fabritius. Yep, that’s the one! In a fateful twist of events, Boris reappears, drags our hero off to Amsterdam--on the eve of his marriage to one of the Barbour girls--for what becomes the most frenzied & exhilarating part of the novel. They have a violent & deadly shootout with some mobsters; Theo’s consequently stricken with fever and its accompanying nightmares--in part due to the traumatic unfolding of events; and I’ll leave the conclusion for those anxious enough to step into a novel close to spanning 800 pages.

***

But any review of Tartt’s monumental novel--both in length & success--would be incomplete without a brief foray into the controversy that has subsequently sprung up around this award-winning, New York Times best-selling, phenomenon that has already (unsurprisingly) sold movie rights. Though it’s not uncommon for critics to diverge on their assessment of any given fictional work, it’s not as common for the deviation to be so wide and fierce.

Three of the major antagonists include: Francine Prose of The New York Review of Books, Lorin Stein of The Paris Review, and James Wood of The New Yorker.

Francine Prose who in The New York Review of Books wrote: “The novel contains many such passages: bombastic, overwritten, marred by baffling turns of phrase, metaphors and similes that falter beneath the strain of trying to convince the reader of a likeness between two entirely unrelated things.” And again:

Throughout The Goldfinch are sections that seem like the sort of passages a novelist employs as placeholders, hastily sketched-in paragraphs to which the writer intends to go back: to sharpen the focus, to find a telling detail, to actually do the hard work of writing. If we readily grasp a scene that Tartt is setting, it’s often because her streetscapes and interiors are not merely familiar but generic.

James Wood from The New Yorker makes scathing remarks toward Tartt’s novel too; saying, for instance: “Its tone, language, and story belong to children’s literature,” or that it contains “too much straightforward genre stuffing” and “the borrowed emotion of the plot often finds exact form in easy, familiar gestures.”

Two of the most bandied about barbs by Lorin Stein, editor of The Paris Review, include: “A book like The Goldfinch doesn’t undo any cliches--it deals in them” (ouch!) and “it coats everything in a patina of ‘literary’ gentility”. In an industry that can sometimes seem pollyannaish--in an attempt to bolster national readership--Stein refuses to yield to the mass hysteria of Tartt-mania.

Several other reviewers have made similar observations--even those amenable to her success: “My main problem with Donna Tartt,” writes The Rumpus reviewer Kiesling, “...I find [her] guilty, somehow, of simultaneously relying on shorthand, belaboring certain points, and generally being unconvincing.” Crum, who defends Tartt’s novel in the Huffington Post, even admits that The Goldfinch is not “especially complex.” But, from her perspective, that only lowers “the barrier of entry into the world she’s created”. Nazaryan’s scathing News Week review titled “Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch Neither Sings Nor Flies” calls The Goldfinch Tartt’s longest and “least mature” novel, adding, “Dull’s the word for the characters, the plot, even the language”. Nazaryan’s diatribe doesn’t end there:

If the novel is Dickensian, as some critics have suggested, then it is only so in the worst possible sense: too long, too often artless. It is like one of those pretty paintings executed with technical skill and yet lacking whatever ineffable quality we ascribe to greatness.

Or maybe that quality is not so ineffable, after all. The novel lacks relevance; it hews to outworn convention in a way that prevents Tartt from saying anything new about people or literature or painting or the rather complex business of being alive.Despite the enthusiastic praise from titans like Stephen King:

"The Goldfinch is a rarity that comes along perhaps half a dozen times per decade, a smartly written literary novel that connects with the heart as well as the mind. I read it with that mixture of terror and excitement I feel watching a pitcher carry a no-hitter into the late innings. You keep waiting for the wheels to fall off, but in the case of “The Goldfinch,” they never do."

And Michiko Kakutani: “A novel that pulls together all her remarkable storytelling talents into a rapturous, symphonic whole and reminds the reader of the immersive, stay-up-all-night pleasures of reading”; the novel, for this reviewer, felt glib & interminable. Though, to be fair, with a tome-sized volume like The Goldfinch, it would be ungracious to leave out a positive remark regarding the incredible stamina Tartt exhibits in carrying a story out so long. In doing so, there are exceptional flares of brilliance, literary adeptness, muscular dialogue, and characters at once unique and sometimes dimensional.

Comments